|

| Ethnically-diverse friends ≈ Positive cross-ethnicity attitudes |

Here are some problems

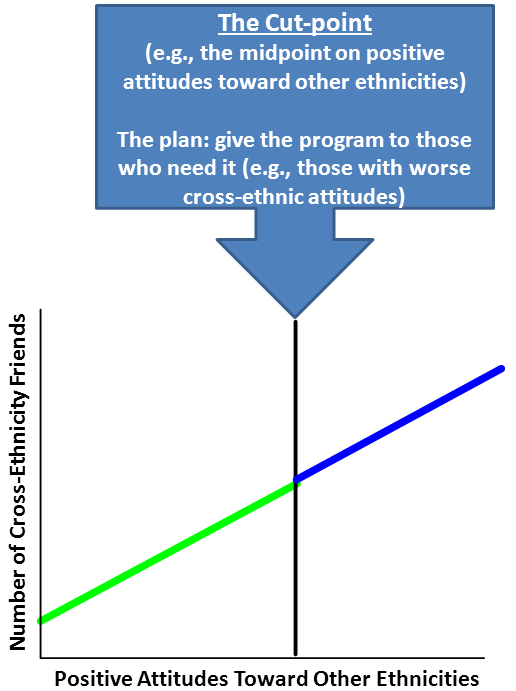

- Not everyone has the same need for the program. Based on our example, some already have relatively positive attitudes toward those from other ethnicities. Therefore, if you put everybody through the program, that might waste time and money.

- To demonstrate the proposed causal link between one’s number of inter-ethnic friends and one’s positive inter-ethnic attitudes, you can’t do so experimentally, given that you can’t randomly assign people to have a greater number ethnically-diverse friends.

So what are you going to do?…

- To target those in need of your program

- To test the effectiveness of your program

In this post

- What the heck is regression disconti-whatever-you-call-it?

- Why bother?

- The big idea

- The design in action

- Caveats

- Why don’t we use this design more routinely?

Why bother?

- Experimental testing, using random assignment to the program (vs. a control condition), is impossible (read, “you’re probably doing research in the real world, not a lab”).

- Random assignment would be unethical (e.g., withholding a potentially useful program from those who need it most, merely to create a control group).

- Random assignment would be a waste of resources (e.g., why give a program to those who don’t need it?).

The Big Idea

The design in action

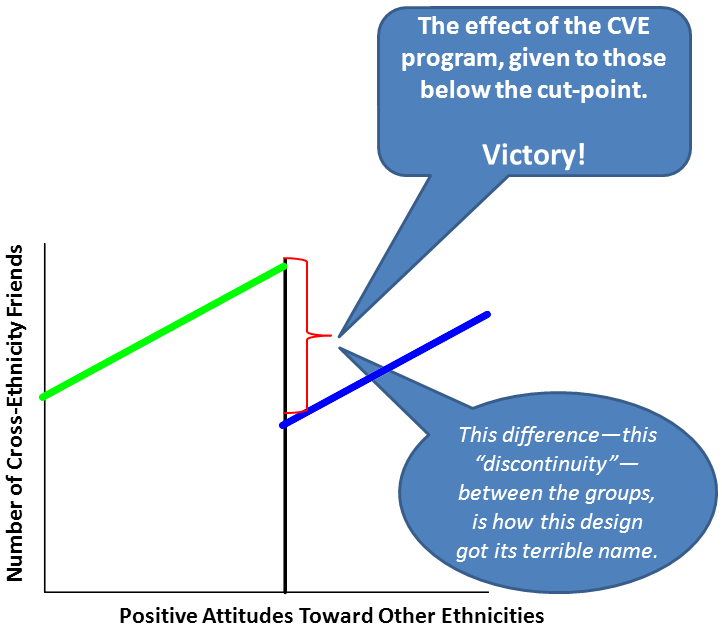

If the program is successful…

If the P/CVE program improves attitudes toward those from other ethnicities, the data will look like this.

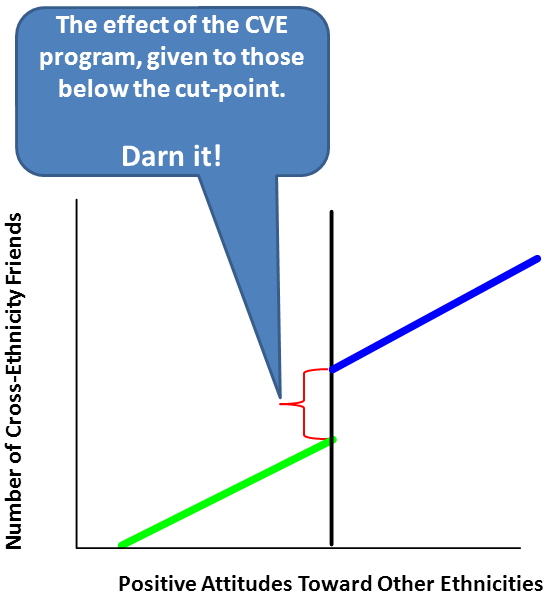

If the program is unsuccessful…

Caveats

2. Respect the cut-point. It’s important that those falling on one side of the cut-point indeed receive/don’t receive the program as intended. If you bend the rule by admitting some people to the program who weren’t intended to get it (or vice versa), you weaken the statistical power of this design and impair your ability to find statistically significant effects.

Why don’t we use this design more routinely?

Researchers, for your consideration:

This technique has been around since the 1960s (shout out to its creators, Campbell and Thistlewaite). According to research methods meister, Thomas Cook, it isn’t used more commonly because it hasn’t been widely taught (though, this is changing).

In his opinion (and mine), when randomized control trials are impossible, researchers should always consider using a regression discontinuity design. (However, there are other strong non-RCT designs; see this blog’s “No control group, no big deal, part 1 (of 2): Propensity score matching designs.”)

Compared with RCTs (which designate people to programs merely on the basis of chance, like playing the lottery with others’ lives), an RD design is a way to test a program by giving it–in an accountable way–to those deemed most in need of it.

In other words, this design is not only ethically desirable, but can save time and money by offering a given program to those deemed most in need.

Additional resources

An in-depth, though highly accessible, overview of RD designs (including several graphics), by a venerable authority on research design, William M.K. Trochim: http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/quasird.php.

A how-to guide for analyzing RD data using SPSS software: http://core.ecu.edu/psyc/wuenschk/SPSS/RegDiscont-SPSS.pdf

Have an idea for a future feature on The Science of P/CVE blog? Just let us know by contacting us through the form, or social media buttons, below.

We look forward to hearing from you!

All images used courtesy of creative commons licensing.